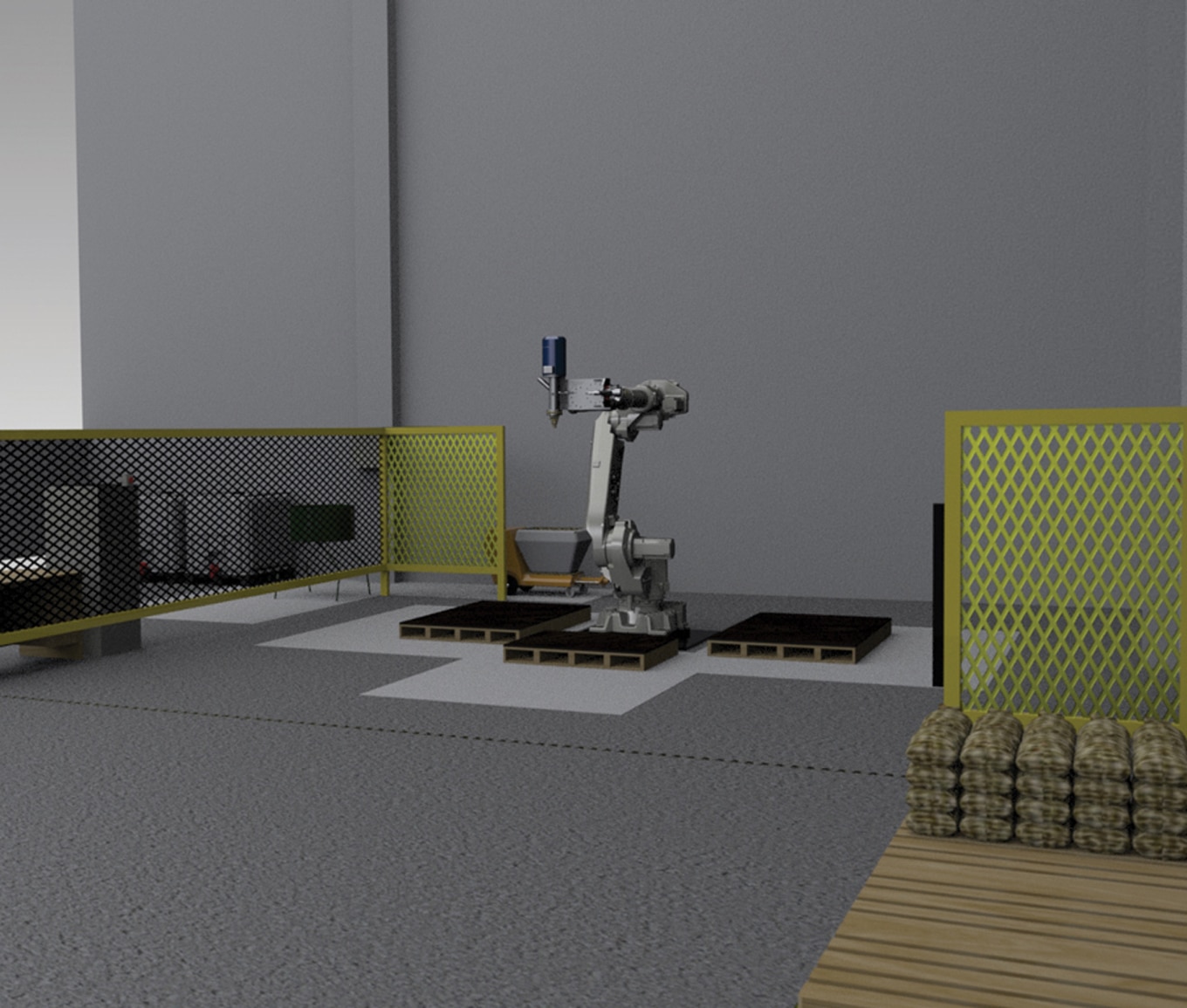

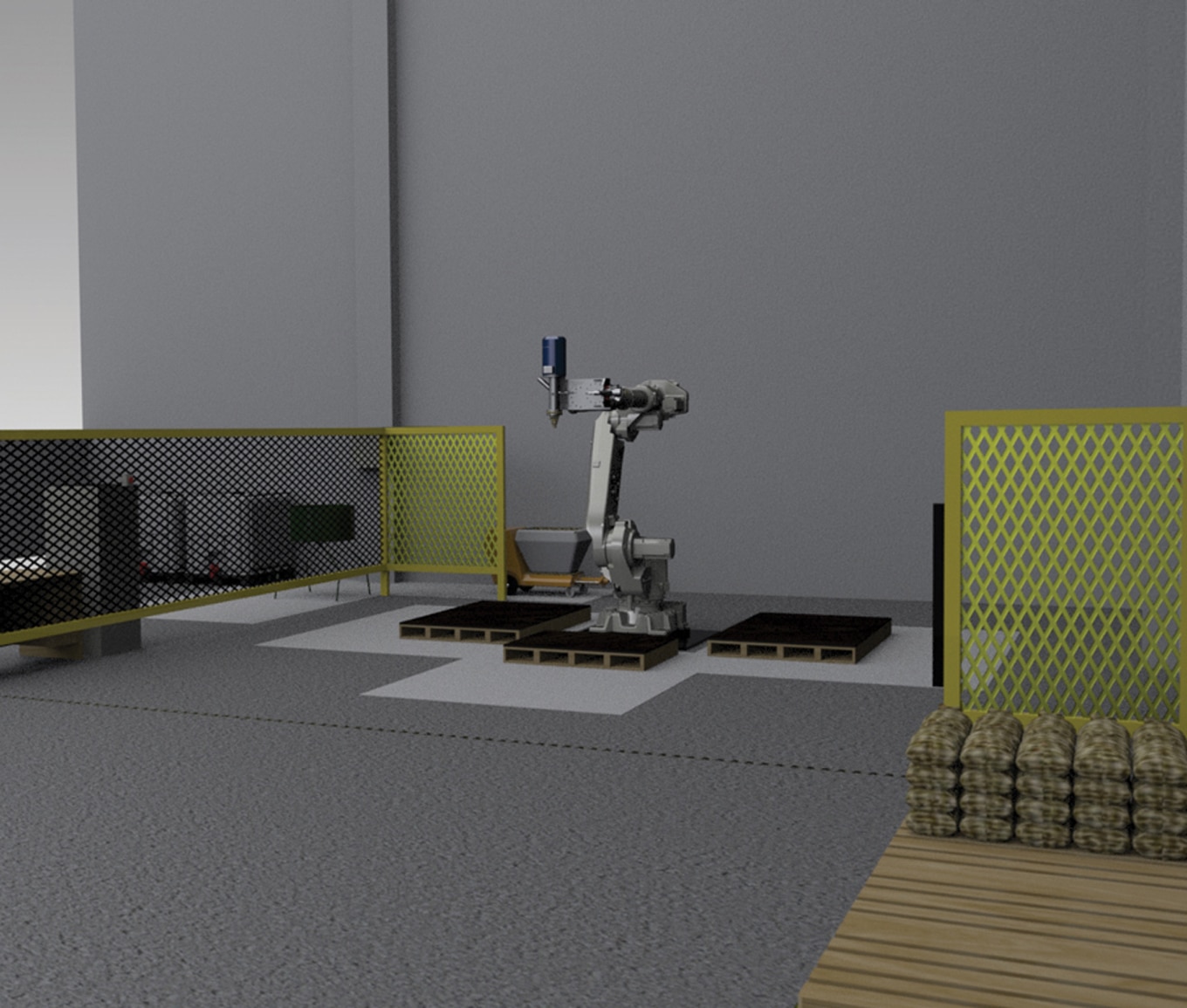

Central to the modular debate is the issue of how mass-produced elements can be made to work with creative architecture. One area that might offer a solution is 3D printing. At the Manufacturing Technology Centre in Coventry, Skanska UK is helping to pioneer concrete printing — a process by which elements can be made in an almost limitless number of shapes and sizes by extruding specialized concrete via a robotic arm.

“Architecturally, the potential of this technology is very exciting,” says Sam Stacey, Skanska’s director of innovation. “To be able to create completely bespoke concrete elements cost-effectively opens the way, for example, to cladding that continuously varies to suit the internal and external environment. You can have whatever shape or angle you want — including shapes that are impossible to make with conventional moulds.

“There is absolutely the potential for this technology to be used in conjunction with volume-produced [moulded] elements. These too are increasingly being made with the help of automation — and in a way 3D printing is just part of that development. Also, the business case for all forms of automation is improving — partly because the cost of the software needed to take a design, and instruct robots to make it, is falling sharply.”

There are technological hurdles to overcome, however, before 3D printing can become a regular feature of modern construction. One such is the corrugated or “corduroy” appearance of 3D-printed concrete. This is a result of the printing process, which builds elements by laying down a 12mm-diameter bead of concrete. “Obviously a smaller bead results in a smoother appearance,” says Stacey. “But smaller beads inevitably slow the whole process and also restrict the size of aggregate you can use. It’s all about finding an optimum balance.” Various approaches are being taken to create a smoother finish, including fitting a trowel attachment to the concrete nozzle, applying a skim, or smoothing the element post-curing by grinding.

Another issue is reinforcement. Again, a number of techniques are being researched, including adding chopped fibre reinforcement to the concrete mix. “Another approach is that the panel can be designed and printed with voids,” Stacey says. “These can be used to introduce steel reinforcement which can then be post-tensioned.”

Skanska envisages 3D robots operating on site, as well as from factories. “We tend to deal with heavy things,” says Stacey, “so printing on site reduces transport costs. A limiting factor at the moment is that the robots we use are very heavy. It would be great to have a hard-working robot trundling around a building — but at the moment it would be liable to fall through the floor.”

While 3D-printing robots will probably start their construction careers in factories, Stacey expects their power-to-weight ratios to improve. “It would also make sense to have them located at a temporary factory near to site,” he says. “That way you get the efficiency associated with off-site prefabrication — but with minimal transportation costs.”

About the Author

This article is written by Tony Whitehead

Read the original post here.